How I Beat the Market as a Busy Surgeon Through Stock Picking - Part 1

I started investing when I was about 10 years old. I still remember the very first stock I bought, which was a telecommunications company that went on to bankruptcy. Thankfully, this did not deter me from continuing to be obsessed with investing. Throughout college and medical school, I enjoyed reading about business and finance, and had a front-row seat during the great financial crisis as we were coming out of college. I really started investing at the beginning of residency, when I started to make my own money.

As an engineer by training, I love data. You cannot improve processes if you can’t define what you are optimizing for, and if you don’t measure it. Thankfully, from the beginning of my investing journey in 2015 or so, I have kept track of every single stock trade I’ve made.

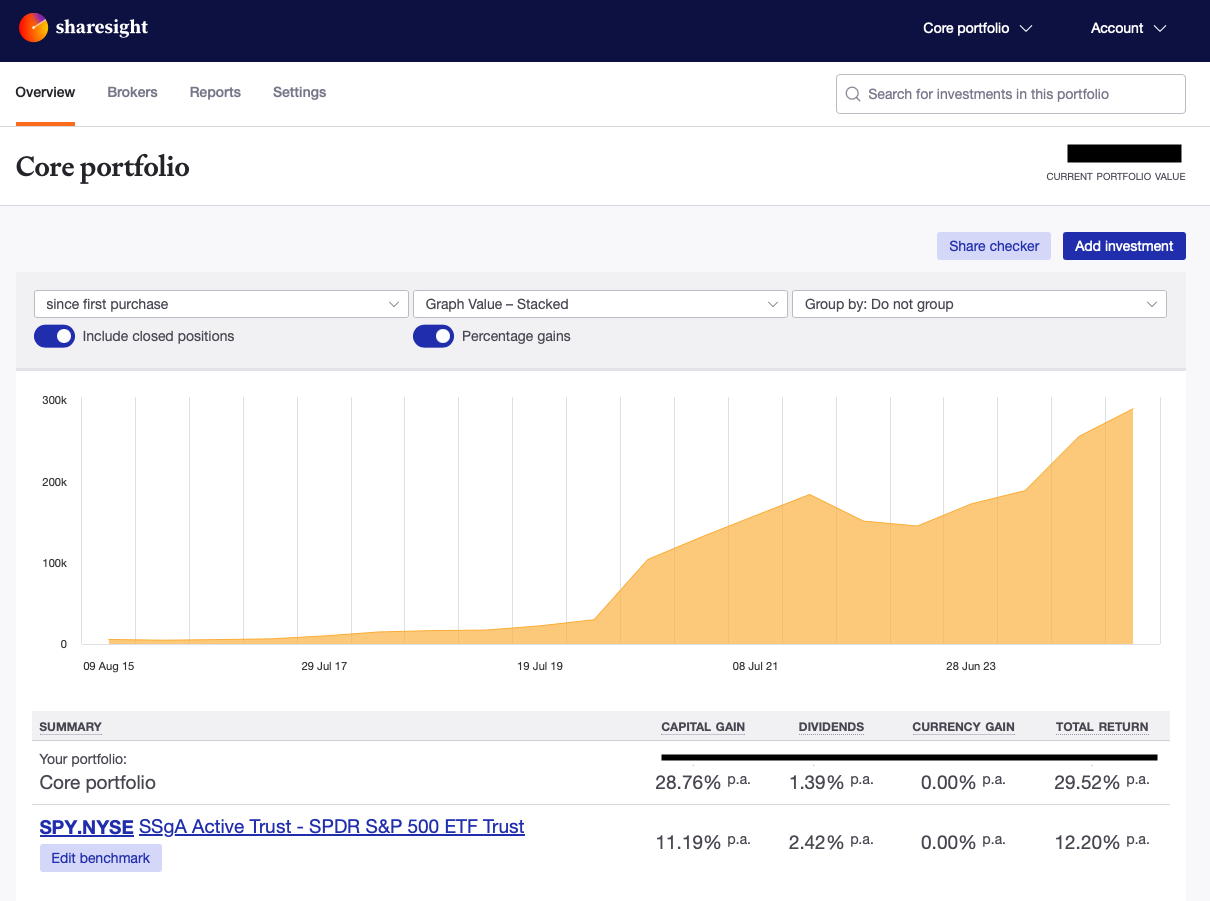

Even with all of the trade data, it is difficult to truly measure performance as an investor. It gets very complicated when you consider not only buying and selling decisions, but dividends as well. A few years ago, I found a service called Sharesight that does just that. You put in your trades, and it figures out the rest, giving you capital gains, dividend returns, and benchmarking against common indices.

This is a recent screenshot of how my individual stock portfolio has performed since 2015 versus the S&P 500.

I’ve read nearly every book I can get my hands on about personal finance, investing, picking stocks, and index funds. I know the data shows that over long time horizons, professional active investors have a very low chance of outperforming the market, especially after fees and taxes. And yet, over close to a decade, my portfolio has compounded at 29.5% CAGR vs. 12.2% for the S&P.

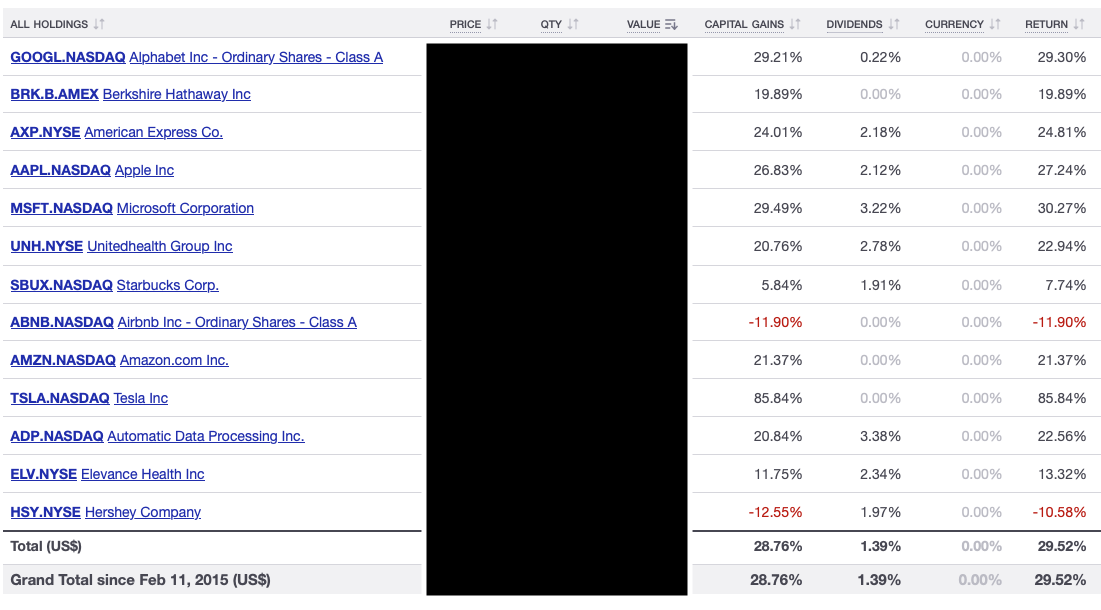

At the same time that the above screenshot was taken, here are the stocks that made up the portfolio, and the annual returns for each stock since first purchase. These are all capital-weighted returns.

From a statistical standpoint, I still don’t think I can say for certain if this is just luck or if I have actual statistically significant skill. Another caveat here is that the majority of our equity allocation is in index funds. As I’ve gotten busier with my surgical practice, I’ve devoted less time to stock picking and so the percentage of our net worth in individual stocks continues to gradually shrink over time. Nowadays, I typically come up with only 1 or 2 individual stock ideas per year. With that out of the way, let’s go over my thoughts and approach on stock picking, and why I think it is very possible to outperform the market with the right framework and temperament.

What are your chances of outperforming the market?

According to the SPIVA (S&P Dow Jones Indices) report, over a 10-year period, 90% of actively managed large-cap funds underperform the S&P 500. Over a 20-year period, that figure rises to 95%.

Looking to hedge funds, according to the HFR Global Hedge Fund Index data, hedge funds have consistently underperformed the S&P 500 since 2008, with an average return of 6.4% vs. 13.6% for the S&P 500.

This data is often cited by proponents of index fund investing. Why spend all the time researching and picking stocks when you can get the market average with no work and outperform most “active managers”?

The key is that you are not an active fund manager. Yes, the average fund manager is probably earning more personally than the average surgeon, but it is much easier to manage money as an individual investor.

The advantages of being an individual investor

Yes, the professional or institutional investor has a lot of resources, most importantly time (this is their job), experience, technology, research, and access to proprietary (not insider) data. Edges in investing can be grouped into several categories: informational, analytical, and behavioral. While conventional wisdom would say that the professional investor must have the edge, I’m not sure if that’s always the case.

The biggest potential advantage for the individual investor is behavioral, but this is a double-edged sword. With the right approach and temperament, this can be a tremendous advantage and could outweigh nearly everything else. But if the individual investor cannot manage their investing behavior appropriately, they would certainly be better off in an index fund.

The advantage lies in the fact that the individual investor can act in their own sovereign interest, because they are investing only their own capital. They have no one to answer to. Conversely, professional managers are investing other people’s money. This is a huge difference. Outside investors can be very fickle, and most likely they lack the temperament to be patient, long-term investors. A fund manager might identify a great stock pick, but it can take months, quarters, and years for the thesis to play out. The manager has done the work so they have the conviction to wait, but the outside money does not. Fund managers have a pretty short leash. If they underperform the market or their peers over a few quarters, their investors will take their money elsewhere. This inevitably colors every investment decision that’s made. They need quick wins. They need to stick with picks that their investors can understand. It is better for them to fail conventionally than to try to succeed unconventionally.

Once the individual investor has identified an opportunity, they don’t really have to explain it to anyone besides maybe their spouse. If the investment is taking a while to pan out, they don’t have to write quarterly reports and letters urging their investors to be patient. They can build their own conviction and just watch the story develop. They can even double down on the position if the price continues to go down before it gets better. And if the story changes and the stock is no longer a good investment, the individual investor can sell and move on without any baggage from having had to justify the pick to outside investors previously.

In addition, professional investors are managing much larger pools of capital. That means their opportunities can be limited to only very large companies that have the market capitalization and volume to handle the amounts that would make a meaningful difference to a large fund. For Berkshire Hathaway, for example, in terms of position sizes that would make a difference, they might be limited to only about 100-200 companies globally just based on size alone. Meanwhile, for the individual investor, the world is your oyster. I once invested in a tiny furniture company that had a market cap of only about $150 million.

Finally, the individual investor might actually have informational and analytical edges over the fund manager. This is the “buy what you know” ethos talked about by Peter Lynch. Just by spending time on earth as a human being, we all develop domain expertise in whatever we spend our time doing. We all only have 24 hours in a day. The stay-at-home mom certainly knows more about baby products and strollers than a hedge fund manager. The vascular surgeon will know more about why one company’s stent might be better than another’s. Even the couch potato would probably know more about the latest video games and pizza delivery. Being the consumer of a product can provide valuable insights into the investing prospects of the company that makes it.

Case example - UnitedHealthcare

Academic talks at medical conferences are often accompanied by case examples to illustrate the take home points. A case example here would be UnitedHealthcare (UNH). It is the largest healthcare company in the world and a component of the DJIA. It is a highly profitable company in a regulated industry, with pricing power. It is relatively capital-light. It has all of the advantages of an insurance company that Buffett often discusses, including having a large float. The stock has compounded annually at 22% from 2000 to 2019.

In 2020 during the Covid pandemic, the price of UNH stock fell precipitously along with the broader market, with a peak to trough decline of -45.8%. I was sitting at home looking at the stock, because the hospital was closed and no elective surgeries were happening. The stock price didn’t make sense. UNH was still collecting insurance premiums, but not paying out medical claims and elective procedures. 2020 turned out to be a great year financially for the company with a great medical loss ratio (MLR). This was quite obvious from my perspective, sitting at home with no surgeries to do! That’s when I initiated a stake in UNH, buying through March and April of 2020. The price of the stock quickly rebounded along with the broader market.

Then in the first part of 2024, another opportunity presented itself. A subsidiary of UNH, Change Healthcare, was hacked and shut down for more than a month. It is an intermediary for medical claims payments between insurance companies and providers. This was incredibly disruptive to our hospital. Suddenly there were no payments coming in, and practices were very disrupted. Some practices even had to take loans out to stay afloat while the backlog was sorted out. The stock again took a hit due to the negative press, but financially, this simply meant their outflows were being delayed temporarily. This is financially positive for the insurance company! I added to the position again, and it quickly rebounded.

In future parts of this series, I’ll go into more case examples of how I picked certain investments and how I managed buy and sell decisions. With the right approach and temperament, however, I believe it is quite possible to outperform the market, sometimes even quite handsomely.